FORCLIME

Forests and Climate Change ProgrammeTechnical Cooperation (TC Module)

Select your language

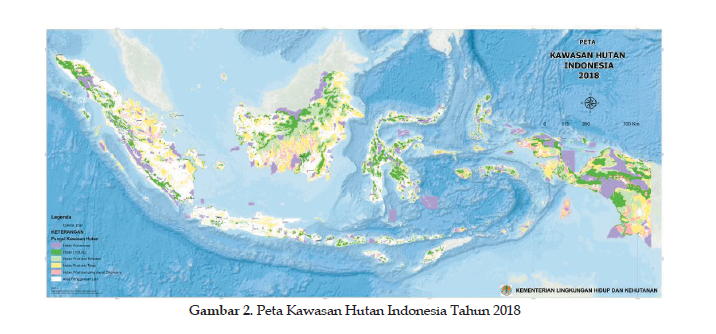

A long-term Indonesian forestry plan document, called National Forestry Plan (RKTN) for 2011-2030 has been issued in 2011 through the Minister of Forestry Regulation Number P.49/Menhut-II/2011 dated June 28, 2011. The issuance of Law No. 23 of 2014 on Regional Government and other strategic forestry related topics on national, regional and global level has created the need to adjust and revise the RKTN.

The evaluation and revision processes were coordinated by the Directorate General of Forestry Planning and Environmental Governance through serial discussions, data and information updating, as well as public discussions and consultations with various parties and stakeholders. The plan was developed as a spatial based plan to show the current situation of state forestlands and provide directions in their utilization. Stakeholder engagement in the processes were conducted at national and sub-national levels.

Source: RKTN 2011-2030

Source: RKTN 2011-2030

FORCLIME supported and involved the process of RKTN evaluation and revision by providing both experts and expertise until its gazettement. The first revised RKTN 2011-2030 was issued on 31 July 2019 through the regulation of the Minister of Environment and Forestry (P.41/MENLHK/SETJEN/KUM.1/2019). Thus, the Plan become a general guideline and reference for Indonesia's forestry development. Dissemination of the revised RKTN regulation has been conducted on 6 November 2019 attended by around 200 participants from the ministry and related stakeholders at Manggala Wanabakti Building in Jakarta.

Article 1 of the regulation on the National Forestry Plan 2011-2030 contains macro directives for the use of forestlands for forestry development and other development that will use forestland at national scale for a period of twenty years.

The vision of the revised National Forestry Planning is “Forest governance aimed to make life support system functioning for people’s welfare”. The vision is further divided into the following missions: 1) Creating adequate forestlands; 2) Reforming forest governance; 3) Performing sustainable multi-benefits management of forests; 3) Improving community engagement and access to forest management; 4) Enhancing environmental carrying capacity; and 5) Strengthening forestry positioning at national, regional, and international levels.

Source: RKTN 2011-2030

Source: RKTN 2011-2030

The Director General of Forestry Planning and Environmental Management, in the preface of the revised RKTN 2011-2030 , states that this revision has important significance in evaluating the performance of forestry management and development; adjusting the development of paradigms and challenges, national, regional and global strategy; alignment with relevant laws and regulations; forestry management reform until 2030 and a reference for the parties in the implementation of forestry management and development until 2030. He also thanked the support given by the stakeholders including GIZ who had contributed in finalizing the revised National Forestry Plan (RKTN) for 2011-2030.

For further information, please contact:

Wandojo Siswanto, Strategic area manager, Forest & Climate Change Policy

Mohamad Rayan, Technical Adviser, Crosscutting Issues and Conflict Management

The Bukit Soeharto Grand Forest Park (Tahura Bukit Soeharto)

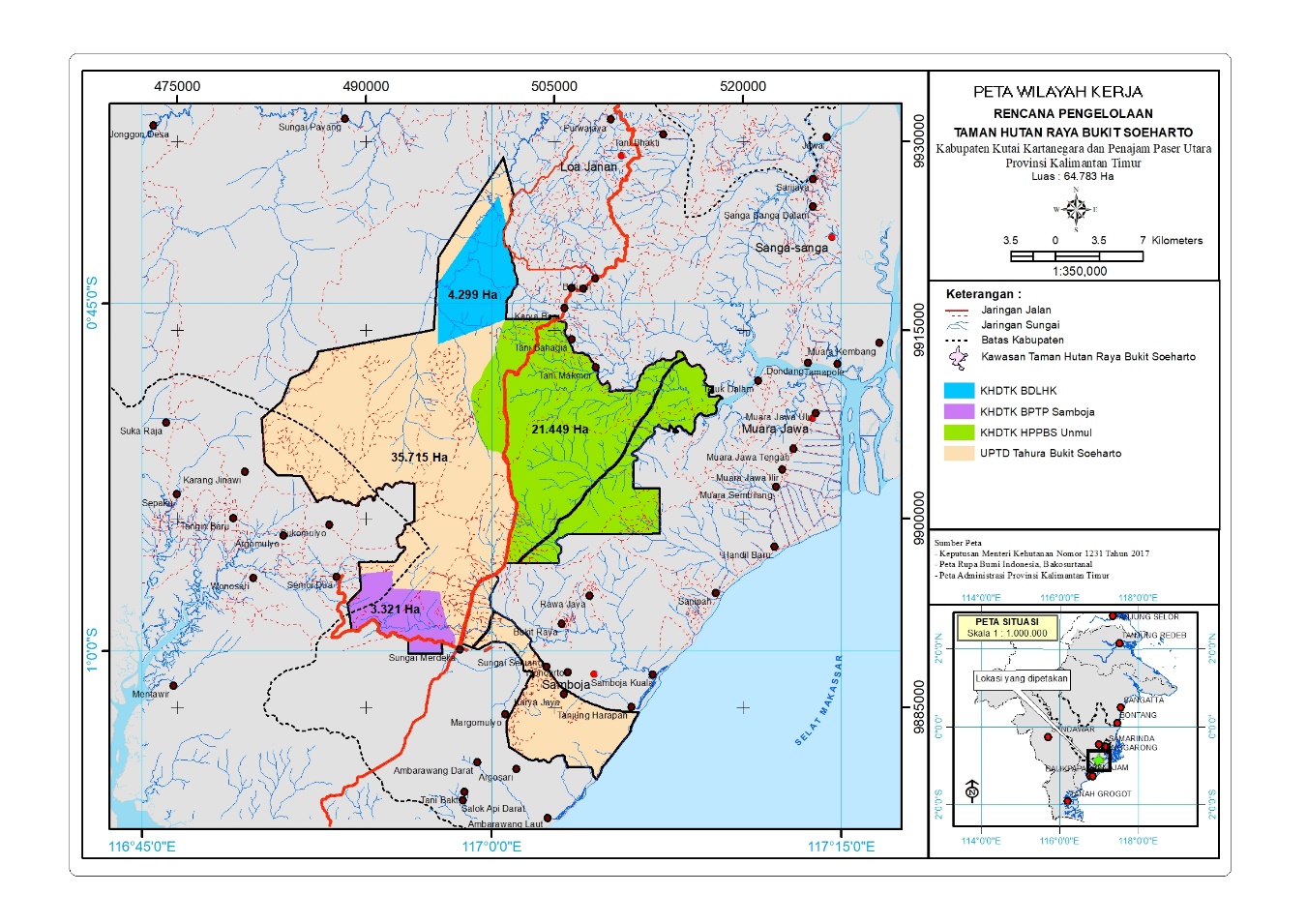

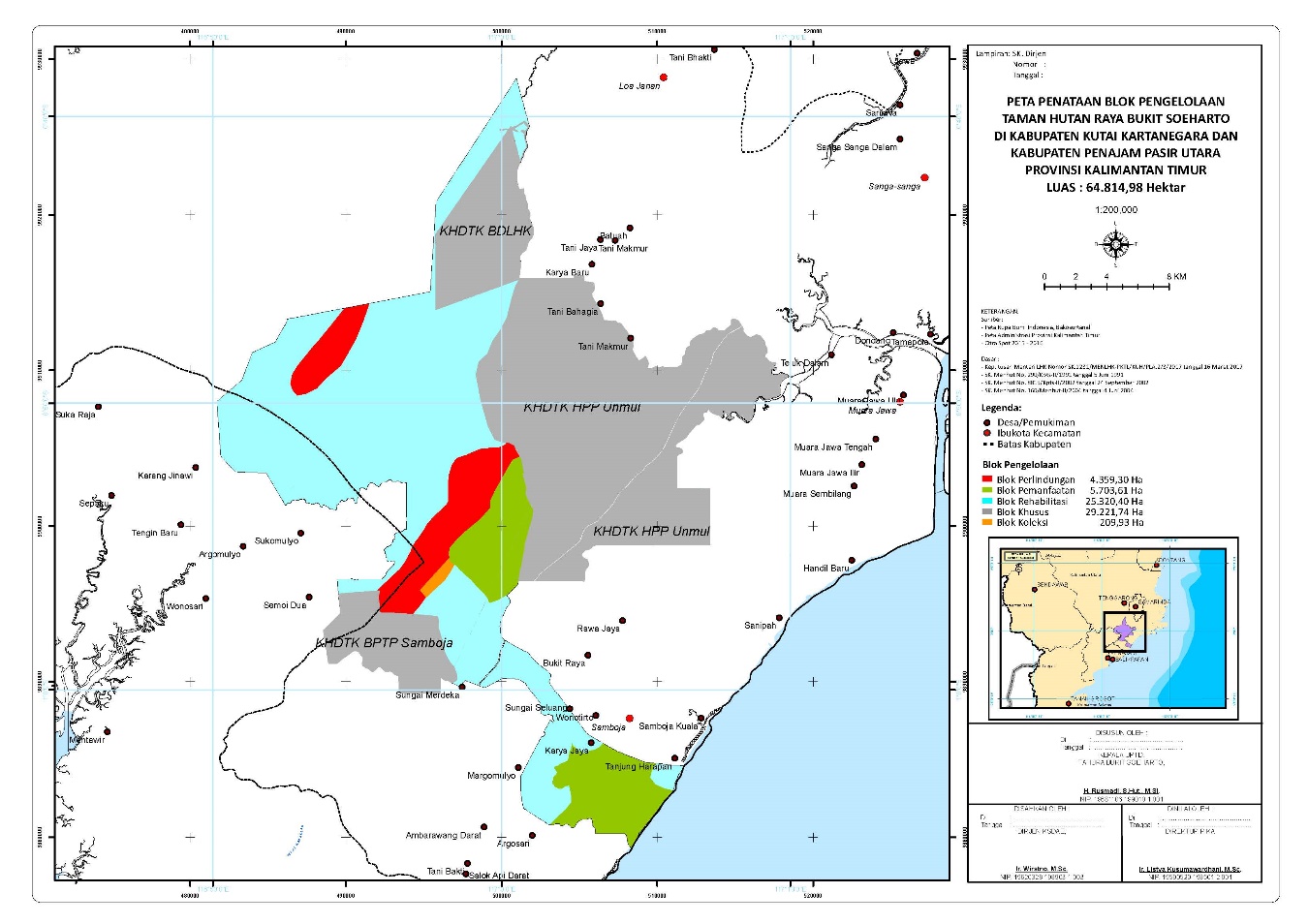

Based on the Minister of Environment and Forestry Decree No. 1231 in 2017, the Tahura Bukit Soeharto covers of 64,814.98 hectares. The Tahura is located in the administrative region of the districts Kutai Kartanegara and Penajam Paser Utara in East Kalimantan Province. Following the East Kalimantan Governor Regulation No. 101 of 2016, the Tahura is managed by the Regional Technical Implementation Unit (UPTD) of the Tahura Bukit Soeharto.

Historical set-up of the Tahura Bukit Soeharto

| 1982 | Decree of the Ministry of Agriculture No.818/ Kpts/Um/II/1982 | Bukit Soeharto Protected Forest was established with a total of 27,000 hectare. |

| 1987 | Decree of the Ministry of Forestry No. 245/Kpts-II/1987 | Bukit Soeharto Nature Recreation Park was established with a total of ± 64,850 hectare. |

| 1990 | Demarcation boundary was completed by the BIPHUT Wilayah IV Samarinda with a total of 61,850 hectare. | |

| 1991 | Decree of the Ministry of Forestry No. 270/Kpts-II/1991 | Determined as Bukit Soeharto Recreation Park with a total of 61,850 hectare. |

| 2004 | Decree of the Ministry of Forestry No.419/Menhut-II/2004 | Determined as Bukit Soeharto Grand Forest Park (Tahura Bukit Soeharto) with a total of 61,850 hectare. |

| 2009 | Decree of the Ministry of Forestry No. 577/Menhut-11/2009 | Changes in Tahura Bukit Soeharto, the area was increased to 67,766 hectare |

| 2017 | Decree of the Ministry of Forestry 1231/2017 revision of the Decree of the Ministry of Forestry No. 577/Menhut-11/2009 | Establishment of Tahura Bukit Soeharto with a total of 64,814.98 hectares, located in the districts of Kutai Kartanegara and Penajam Paser Utara, East Kalimantan Province |

Source: Dokumen Blok Pengelolaan Taman Hutan Raya Bukit Soeharto di Kabupaten Kutai Kartanegara dan Kabupaten Penajam Paser Utara Propinsi Kalimantan Timur periode 2019-2028

Within the Tahura Bukit Soeharto, three special purposes forests were designated (Kawasan Hutan Dengan Tujuan Khusus-KHDTK), namely:

(1). The Samboja forest research area (KHDTK Penelitian Samboja) with a total of 3,504 hectare, which later was transformed into the Seed Technology Research Institute (Balai Penelitian Teknologi Perbenihan) following the decree of the Ministry of Forestry No. 201/MENHUT-II/2004);

(2). The Samarinda education forest (KHDTK Balai Pendidikan dan Latihan (Diklat) Kehutanan Samarinda), whichcovers 4,310 hectare, which are determined through the Minister of Forestry decree. No. 8815/Kpts-II/2002); and

(3). The Universitas Mulawarman tropical forest research center (KHDTK Pusat Penelitian Hutan Tropis Lembab-PPHT) with a total of 20,271 hectare, following the Minister of Forestry decree No. 160/Menhut-II/2004.

As it was originally established as a Grand Forest Park (Taman Hutan Rakyat-Tahura) , the Bukit Soeharto forest area has to be managed in accordance with the regulation of managing a Nature Conservation Area (KPA), of which the main function is protecting life support systems, preserving diversity of plant and animal species and sustainable use of biological natural resources and their ecosystems (Regulation of the Minister of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia Number: P.35/MENLHK/SETJEN/ UM.1/3/2016 concerning Procedures for the Preparation of Management Plans in Natural Reserve Areas and Nature Conservation Areas).

Thus, in its management, Tahura Bukit Soeharto is divided into management blocks in accordance with the Minister of Environment and Forestry Regulation No. P.76/Menlhk-Setjen/2015. In addition, the distribution of blocks also refers to the Regulation of the Director General of Conservation of Natural Resources and Ecosystems Number: P.11/KSDAE/SET/KSA.0/9/2016. The division of management blocks is adjusted to the physical, socio-economic and cultural conditions. The arrangement of the Tahura Bukit Soeharto Tahura management blocks will be used as a guidance in developing a long-term management plan (RPJP) for the next 10 years.

Therefore, a document of for managing the Tahura Bukit Soeharto was prepared with the following objectives:

The document for managing Tahura Bukit Soeharto covers the following information:

FORCLIME’s support

FORCLIME Technical Cooperation (TC Module) played an active role in preparing the Tahura Bukit Soeharto management document, starting from the preparation (coordination meetings, discussions); conducting public consultations; providing GIS experts to conduct spatial analysis, experts to assist with the writing and editing process); facilitating the document evaluation by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry Team (Directorate of Patterning and Nature Conservation Information) and capacity building for Tahura Bukit Soeharto staff through a coaching clinic for planning documents. In addition, FORCLIME is also actively involved in accelerating the endorsement process such as supporting the process of improving post-assessment documents, escorting the process at the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, public consultations and coordination.

Next stage

The documents on the management of the Bukit Soeharto Tahura management block have been validated by the Director General of Conservation of Natural Resources and Ecosystems through Decree No. 415/KSDAE/SET/KSA.0/10/2019 concerning the Management of the Bukit Soeharto Grand Forest Park, Kutai Kartanegara and Penajam Paser Utara Regencies of East Kalimantan Province. Furthermore, it will be used as a guide in preparing a long-term management plan (RPJP) for the next 10 years.

FORCLIME's next supports will be related to preparing the Long-Term Management Plan of the Tahura Bukit Soeharto. FORCLIME is committed to actively support the process during the preparation such as coordination meetings, discussions; conducting public consultations; providing GIS experts to conduct spatial analysis, experts to assist with the writing and editing process); facilitating document evaluation by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry Team (Directorate of Conservation Areas) and additionally, will be involved in accelerating the approval process.

For more information, please contact:

Suprianto, Technical Adviser for Sustainable Forest Management

Wandojo Siswanto, Strategic Are Manager for Forest Policy

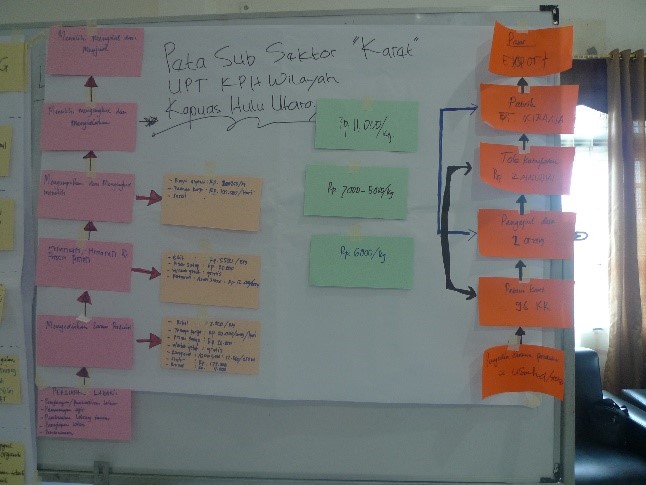

According to FORCLIME’s objectives both capacity development of Forest Management Units shall be supported and living conditions of rural communities be improved. This can be achieved through strengthening of qualifications needed e.g. entrepreneurial capabilities contributing to local stakeholders managing forest resources in a sustainable way. As a couple of social forestry schemes have been granted by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry and more will follow a growing number of local communities are legally entitled to manage these resources independently.

Since entrepreneurship is a broad field a comprehensive programme was needed to cover the most important aspects of the subject. This includes identification of suitable commodities, development of supply chains, means of processing and packaging, marketing of products and cooperation among likeminded farmers. At the same time any business setup should aim on sustainability in order to create long-term jobs and permanently generate income for the actors involved. To ensure a practical approach the training should include theory and practice and at the same time give support looking at individual concepts focussing on potentials existing locally by revising business ideas and providing coaching sessions.

The activity was basically aiming on three target groups:

1. As the ones to develop their own business and generate income local communities were addressed directly. Representatives of different villages should pick up useful knowledge to take home, implement individually but also as multipliers pass it on to other community members.

2. Forest Management units (FMU) are considered to function as public service providers giving technical support to local stakeholders in all matters affecting sustainable forest management and use of natural resources deriving from in and around their forests. For this kind of extension service comprehensive qualifications including entrepreneurial competencies are needed.

3. Teachers of the regional Government Forestry Training Centres (BDLHK) will be the responsible persons to in future regularly provide training to FMU-staff in order to equip them with knowledge needed to fulfil their consulting mission. They should specialize on certain topics to pass on the relevant knowledge and work as moderators supporting forest service extension officers.

The implementation of the training program was entrusted to an Indonesian consulting company, which has the necessary skills and experience. Because participants can usually be made available for a week at the most due to other commitments and obligations it was important to divide the further training measure into several consecutive modules that build on each other. Hence the entire series of training events consisted out of a one-week basic training workshop, follow up by a two-days coaching event that was implemented after several weeks only. For participants, who would later act as multipliers passing on their knowledge to others, a one-week advanced course was also carried out.

The components included different topics to deal with intending to enable participants to acquire basic knowledge and develop simple business models. During the basic workshop the following topics was dealt with:

The last aspect should be further elaborated following the basic course. With regard to a commodity that is available in the participants’ home area a business plan should be developed and elaborated further. During a follow-up event (“coaching workshop”) this concept had to be presented and justified. The group of participants should then question the concept and point out any existing weak points in order to subject it to a reality check.

The last component of the training programme (“advanced training”) was following the train-the-trainer approach focussing on providing deeper insights in business related issues. This kind of knowledge should be given primarily to the representatives of the FMU and training centres in order to strengthen them in their intended role as advisers. The module included topics like:

The latter subject seems to be of utmost importance to promote cooperation and a common strategic orientation of producers of the same commodity. By setting up organizations like associations, cooperatives or any other type of joint platform representing the interests of its members it should be possible to strike a fair balance between the positions of producers and customers and to avoid any unfair dependencies.

All participants mainly originating from West Kalimantan and North Kalimantan got involved with high motivation during the sections of the training programme. Practical exercises with a high relevance to reality focussed on commodities available in the regions including honey, tengkawang (illipe nut), rattan as well as agarwood, cacao and eco-tourism. Since this is just a selection of potential products further research and development as a follow-up is needed. And although the training program was comprehensive and intensive comprising 7 (basic training and coaching) or 12 days (including advanced training), there is a need for further consultation. In future it will be one of the tasks of the Indonesian Forest Management Units to give this advice to the local communities in order not only to encourage production and create business opportunities for rural communities but also provide permanent consultation for necessary adjustments to changing business environments. For this they shall be updated and supported by the regional forest training centres (BDLHK) implementing further training events and transferring additional knowledge and essential information.

For more information, please contact:

Lutz Hofheinz, Strategic area manager, forest management unit development

Mohammad Sidiq, Coordinator North Kalimantan Province

Jumtani, Coordinator West Kalimantan Province

Forests in East Kalimantan

East Kalimantan province possesses an area of 16,732,065.18 hectare, with land area of 12,734,691.75 hectare. Based on the Land Use Plan (RTRW) of East Kalimantan, the forest area makes up to 8,380,308 hectare while the non-forestry area/areas for other purposes make up to 4,319,137 hectare. East Kalimantan possesses forest area with specific characteristic of humid tropical forest which comprised of various forest types, among others are coastal forest, low land dipterocarps forest, and mountain forests and contains of 5 ecosystems: freshwater swamp, karst, kerangas, mangrove, and peat swamp.

Based on the KPH design and post-development of province area, there are 18 KPH Production units, 2 KPH Protection units, 1 Provincial KPH Conservation unit, 1 District Conservation unit, and 5 conservation areas.

Provincial Level Forestry Plan of East Kalimantan

Provincial Level Forestry Plan (RKTP) is the plan containing instructions on macro spatial use, the potency of forest area for forestry development and non-forestry development using forest area, as well as the estimation of contribution of forestry sector in the province area for 20 years span. RKTP covers the whole aspect of forest maintenance including the forestry plan, forest management, research, development, education, training, and monitoring. Due to its long-term nature, RKTP also contains indicative macro instructions.

RKTP of East Kalimantan for 2011-2030 has been appointed through Governor Regulation of East Kalimantan in 2012. However, the progress of regional and forestry development has been very dynamic, and several policies related to spatial and forest management in general have been produced as well since then. Hence, there is a demand to synchronize and adjust the RKTP.

The underlying aspects urging the change of RKTP are elaborated as follows:

Revision of RKTP is authorized through Governor Regulation No. 55 Year 2018. The process of adjustment of RKTP is carried out by Provincial Forestry Service with support from its partners, including GIZ and Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI).

RKTP East Kalimantan is limited to the forest management in the forest area for the span of 2011 – 2030. The development of RKTP East Kalimantan is purposed to give instructions on the forest maintenance in the future, thus enabling to return the multifunction potency of forest and forest area as well as its utilization in sustainable manner for the prosperity of people in Indonesia, especially the people of East Kalimantan, and to give the real contribution in maintaining global environment.

The objectives of RKTP East Kalimantan are:

FORCLIME Support

FORCLIME Technical Cooperation Module has actively contributed in the process of developing the revision of RKTP 2011-2030, such as in preparation (coordination meeting, discussion meeting); conducting public consultation; and providing experts (GIS experts for spatial analysis, consultant to assist the writing and editing process); facilitating the governor regulation making process; and printing the RKTP document. Furthermore, FORCLIME supports the dissemination process of RKTP-related policies such as Governor Regulation 55/2018 on the Revision of Annex for the East Kalimantan Governor Regulation 19/2012 on Provincial Level Forestry Plan of 2011-2030 to the related stakeholders.

For further information, please contact:

Suprianto, Technical Advisor for Sustainable Forest Management

Wandojo Siswanto, Strategic Area Manager for Forest Policy

Kasmiyati, Forestry Service of East Kalimantan

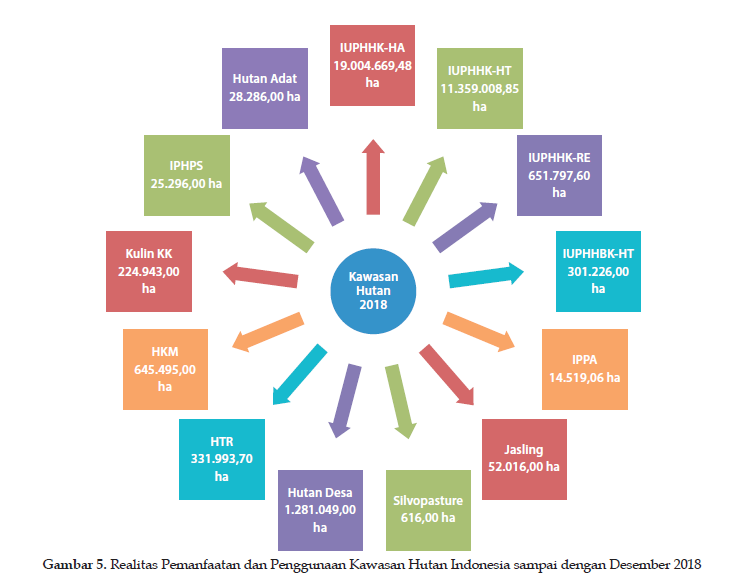

Social forestry is a government program which authorizes the right for communities to manage state forests, customary forests, and entitled forest for the purpose of improving community welfare, environmental balance, and socio-cultural dynamics. The authorization of forest management is conducted in the form of management permits on Village Forests (Hutan Desa/HD), Community Plantation Forests (Hutan Tanaman Rakyat/HTR), Community Forests (Hutan Kemasyarakatan/HKM), Customary Forests, and Forestry Partnerships. The technical guideline for developing social forestry is elaborated through the Regulation of Ministry of Environment and Forestry No. P.83/MenLHK/Sekjen/2016.

As of December 2018, Social Forestry in Berau district covers ± 69.447 hectare, making Berau the district which holds the largest area of Social Forestry in East Kalimantan involving: eight Village Forests; one Community Plantation Forest; and one Forestry Partnership.

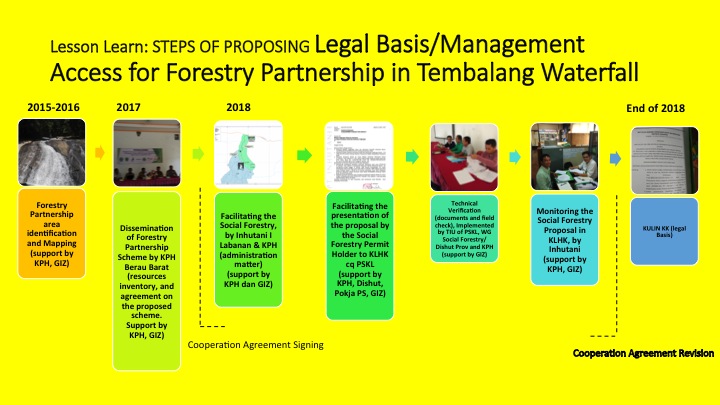

FORCLIME supports the effort for accelerating the Social Forestry implementation in Forest Management Unit (KPH) Berau Barat, including Tembalang Waterfall Forestry Partnership as the effort to resolve land conflicts and improve community welfare.

Forest Management Unit (KPH) Berau Barat

KPH Berau Barat, located in Berau district, East Kalimantan, manages an area of ± 786.021 hectare based on the Minister of Forestry Decree No: SK. 674/Menhut-II/2011. The permit area includes 11 (eleven) Forest Timber Product Exploitation Permits – Natural Forest (IUPHHK-HA), one Forest Timber Product Exploitation Permit – Industry Plantation Forest (IUPHHK-HTI), and one Forest for Special Purpose (KHDTK) in Labanan. In addition, there is one more permit on Charcoal business (Perjanjian Karya Pengusahaan Batubara/PKP2B) from the national level and nine other permits from district level.

The area certainty of KPH Berau Barat is not strong yet. The function of forest areas (in KPH area) is generally still on the allocation stage neither boundaries nor delineation processes have taken place for neither functional borders nor physical borders for the KPH. Thus, there are several overlaps between IUPHHK and mining permits, between settlements (the old settlement and the transmigration settlement), and many other conflicts caused by tenurial matters.

Social Forestry in KPH Berau Barat

The Directorate General of Social Forestry and Environmental Partnership (DG PSKL) on behalf of the Minister of Environment and Forestry has signed the Decree No. SK.8868/MENLHK-PSKL/PKPS/PSL.0/12/2018 on Recognition and Protection of Forestry Partnership between Sadar Wisata Allo Malau Group with PT. Inhutani I Unit Labanan II. The purpose of the Forestry Partnership scheme is to assist the Kampung Tepian Buah community sharing revenues gained by the management of the waterfall tourism management, a waterfall which is located within the forest concession area owned by PT. Inhutani I Unit Labanan. This partnership scheme is referring to the Minister of Environment and Forestry Regulation No.P.83/Menlhk/setjen/Kum.1/10/2016 about Social Forestry.

The area of Tembalang Waterfall forestry partnership is located along Tembalang river. Within the area, there are 3 different waterfalls with a total area of + 225 hectare located in the concession area of PT. Inhutani I Unit Labanan (UMH Tepian Buah) and administratively located within Kampung Tepian Buah, Berau district, East Kalimantan. Based on the function of the area, the Tembalang waterfall forestry partnership lies within a Limited Production Forest (HPT) and is dominated by Dipterocarpacea spp. (a family of mainly tropical lowland rainforest trees used for timber production), and mostly primary and secondary forests. This area is at 150-200m above sea level, with a slope level of 3-15% and wavy topography.

Generally, the partnership includes agreements from each party to share the revenue from the waterfall management; monitoring and evaluation activities about the implementation of the waterfall tourism are conducted periodically.

The forestry partnership has been going on for five years since the Decree was signed and can be extended as long as the validity of the business permit is issued for the IUPHHK-HA PT. Inhutani I Labanan. Furthermore, the extension is based on the result of the evaluation as well as the agreement from both parties. The partnership will be monitored yearly and evaluated every 5 years.

The agreed upon business revenue sharing scheme is as follows: The percentage of a net income of 40% is given to PT. Inhutani I Labanan and 60% to the community /POKDARWIS. The revenue is saved in a special account. The profit from the partnership is given at the end of the year to each party after operational/management costs have been deducted.

Support

FORCLIME supported the activities on the preparation and proposal development to obtain the legal basis for a Forestry Partnership on Tembalang Waterfall Management.

The above-mentioned activities include: area identification, area mapping, raising awareness on the Forestry Partnership scheme, participative mapping, assistance during the process of proposal development, assistance during the technical verification, assistance in preparing and processing the signing of the Forestry Partnership script, training to increase the KPH and community development, assistance in the coordination and communication process between two parties, and support in improving and institutional strengthening for KPH and community institutions.

Way Forward

After obtaining the legal basis, FORCLIME will keep supporting the Social Forestry activity in KPHP Berau Barat via the following activities:

For further information:

Suprianto, Technical Advisor for Sustainable Forest Management

Lutz Hofheinz, Strategic Area Manager for KPH Development

Hamzah, Head of Natural Resources Protection and Conservation, and Community Empowerment (KPH Berau Barat)

|

Supported By: |

|